Introduction

Skin of color patients with psoriasis face unique challenges related to disease characteristics and treatment. Distribution and severity of psoriasis may be greater in patients with skin of color.1,2 Dyspigmentation—including postinflammatory hypo- and hyperpigmentation—also more frequently and severely affects patients with skin of color3,4 and remains a challenge for dermatologists to manage.5 Finally, Black and Hispanic/Latino patients have demonstrated worse health-related quality of life (QoL) compared with White patients, as assessed by the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)6; these differences are likely related to several factors, which include varying cultural perceptions of skin disorders and the greater negative impact of dyspigmentation in patients with skin of color.2,7 The treatment of psoriasis commonly involves the use of topical corticosteroids, such as the superpotent topical corticosteroid halobetasol propionate (HP).8,9 Corticosteroids are anti-inflammatory, immunosuppressive, antiproliferative, and vasoconstrictive; however, tachyphylaxis and adverse events following long-term use remain a concern.8-10 The topical retinoid tazarotene (TAZ) has several mechanisms of action that modulate pathogenic factors of psoriasis—including normalizing markers of differentiation, proliferation, and inflammation—though TAZ used alone may induce cutaneous irritation.10-13 The combination of HP with TAZ may enhance efficacy in the treatment of psoriasis, reduce side effects of both active drugs, and sustain treatment response.10,11

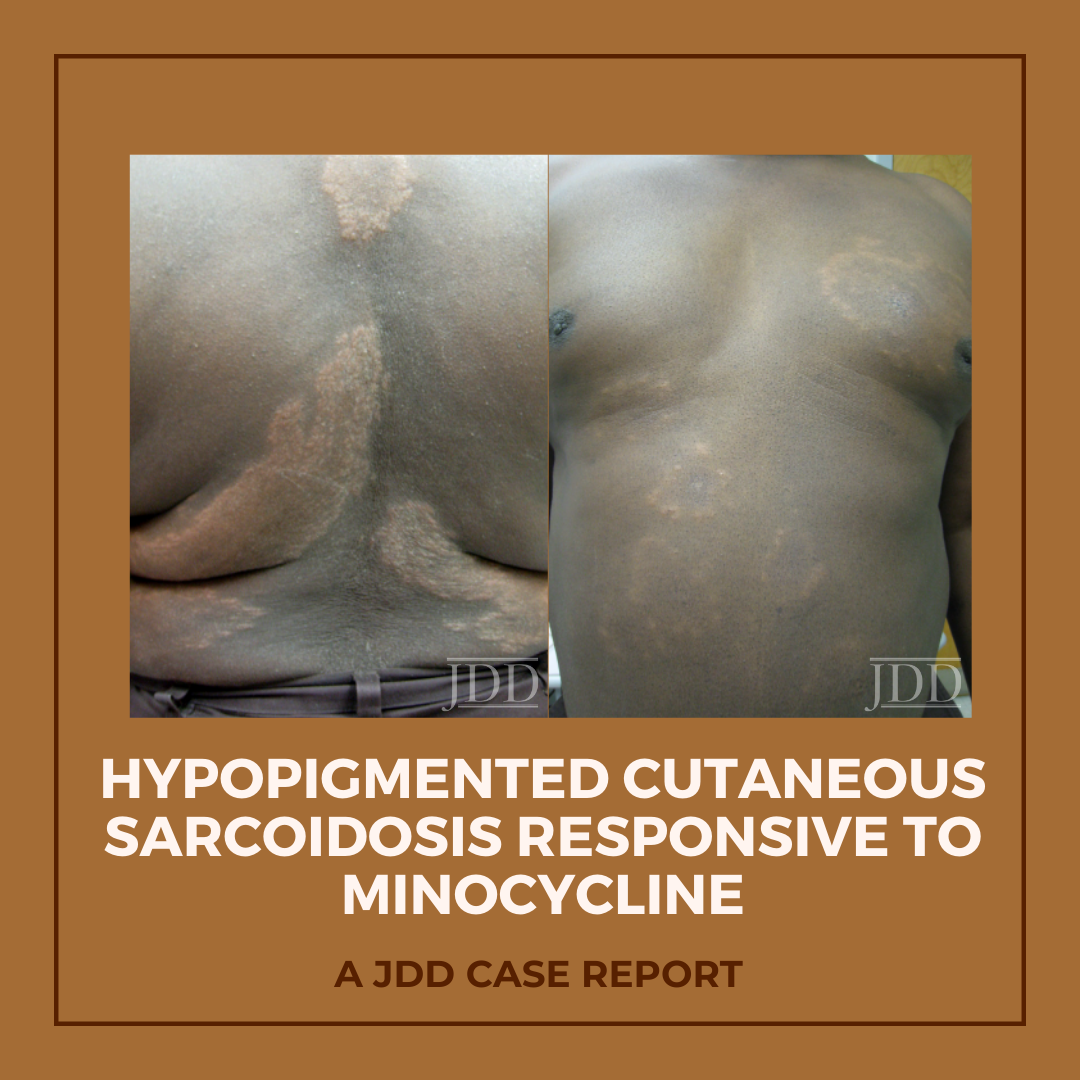

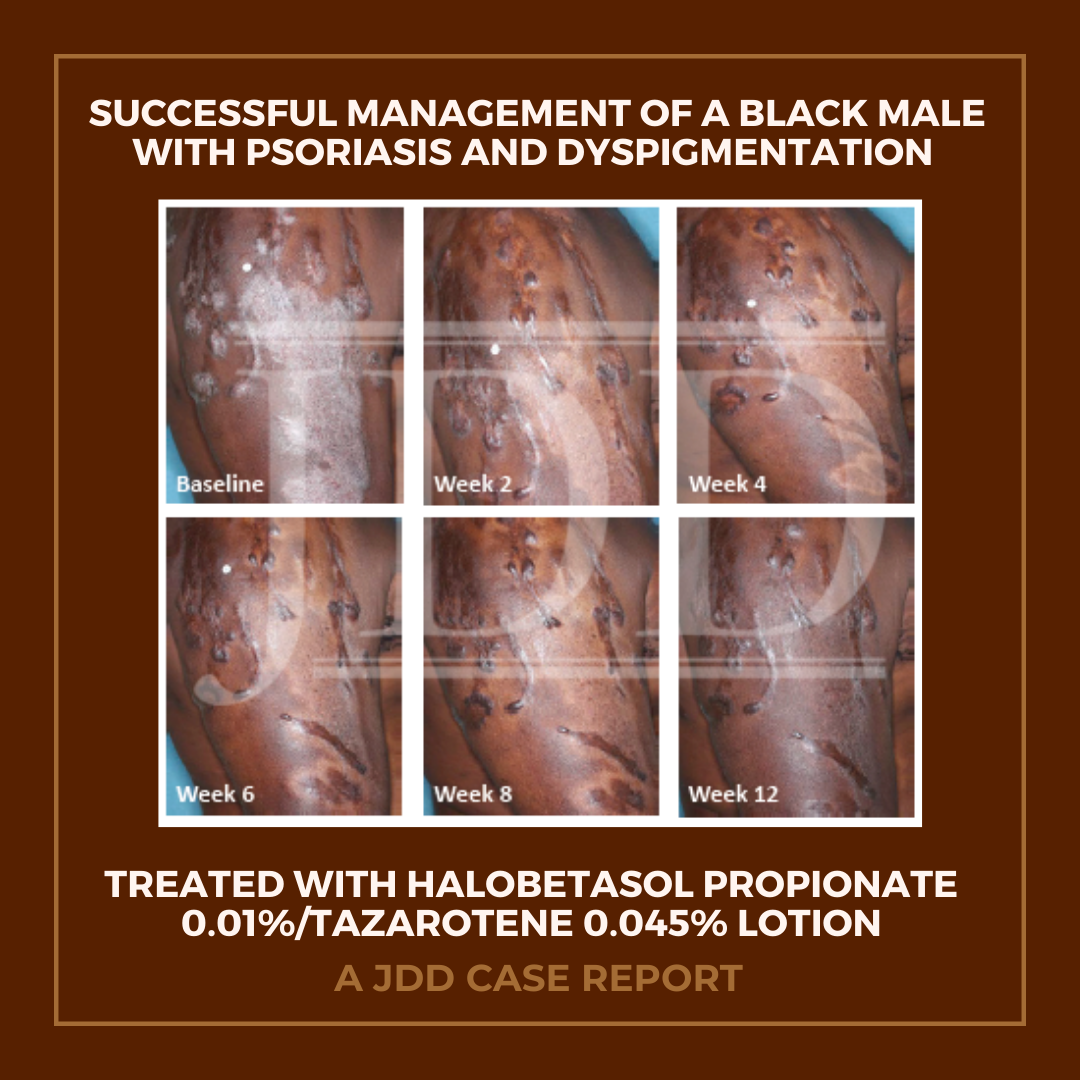

A fixed combination lotion of HP 0.01% and TAZ 0.045% (HP/TAZ; Duobrii,® Ortho Dermatologics, Bridgewater, NJ) was developed utilizing a novel polymeric emulsion technology, which allows for rapid and uniform distribution of HP and TAZ, humectants, and moisturizers on the skin.10 Phase 3 clinical data have demonstrated efficacy and tolerability of HP/TAZ lotion in patients with moderate-to-severe localized plaque psoriasis.14,15 Here, we present a case report of a Black male with moderate plaque psoriasis who was successfully treated with once-daily HP/TAZ lotion over 8 weeks, with resolution of skin dyspigmentation by week 12.

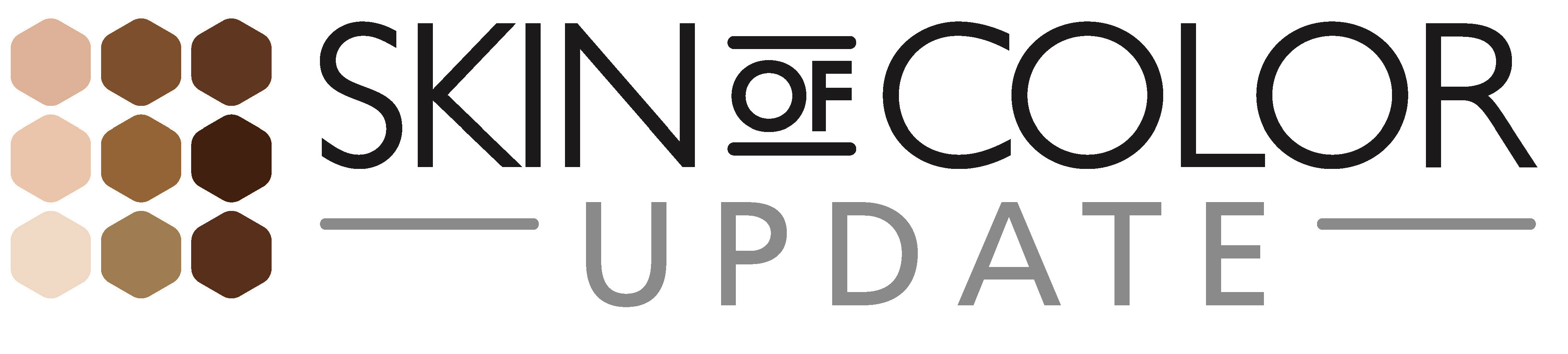

Click table to enlarge

Case Report

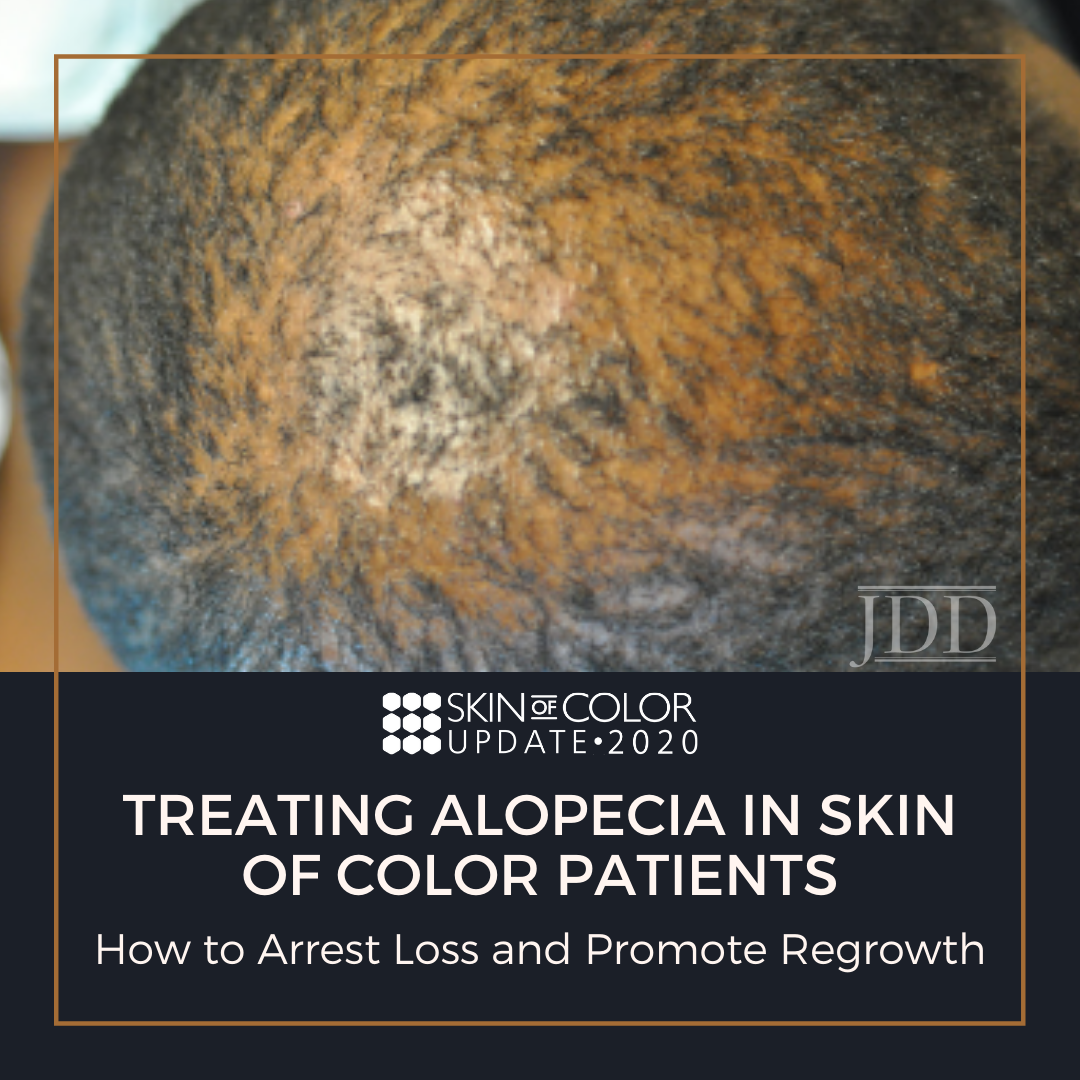

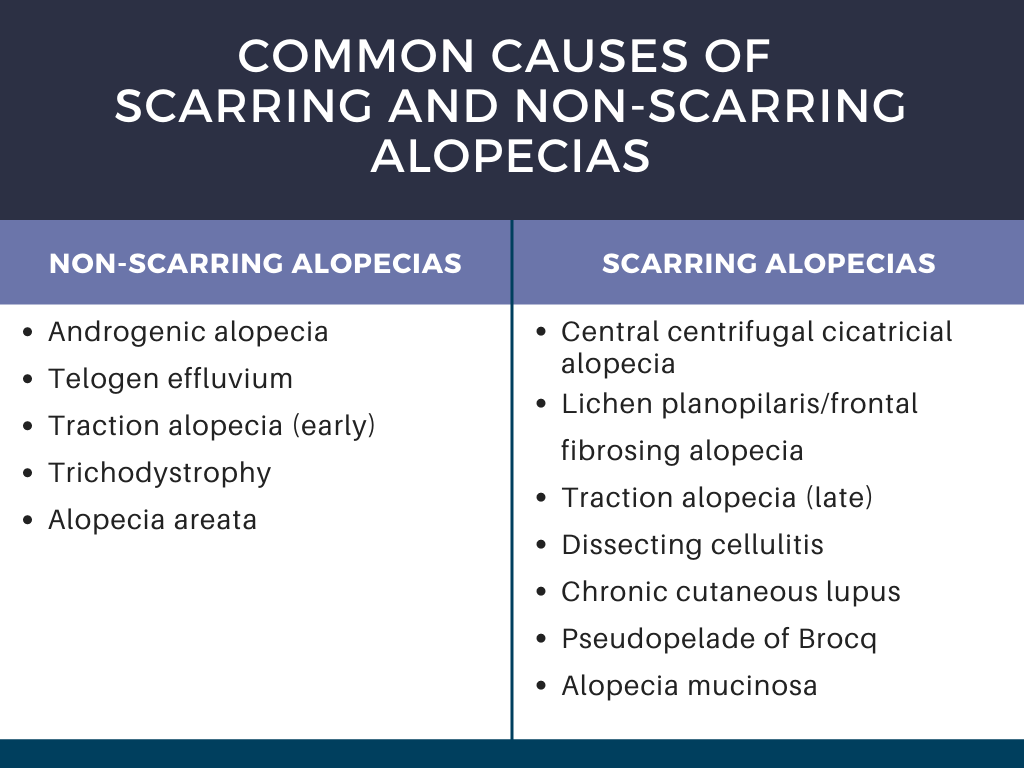

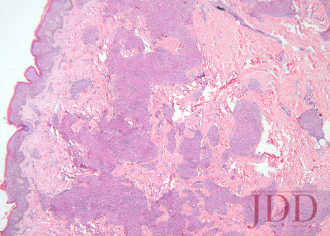

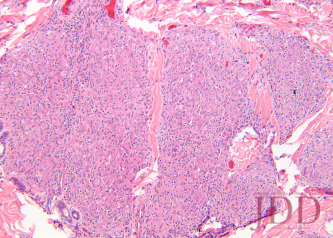

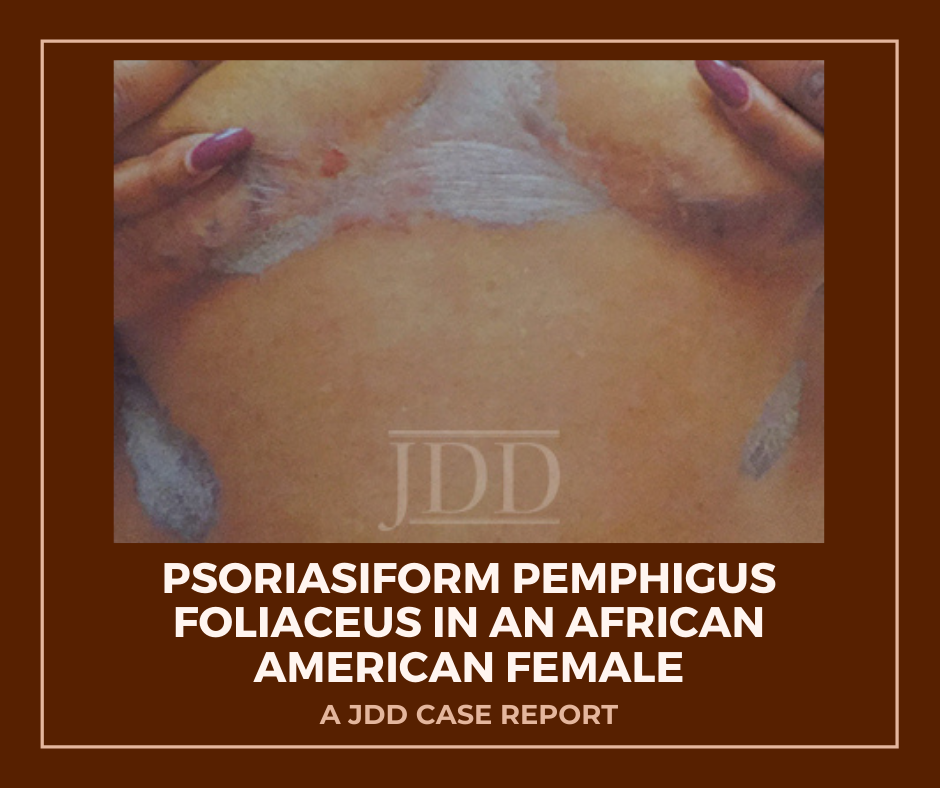

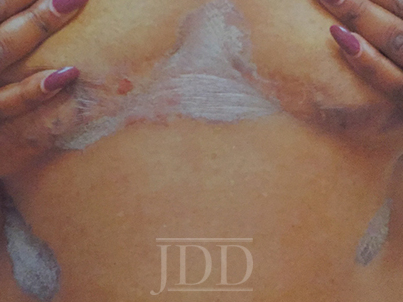

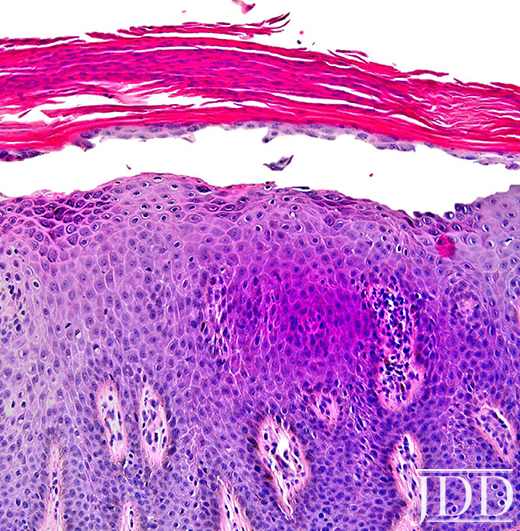

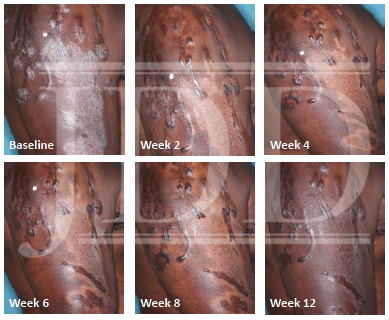

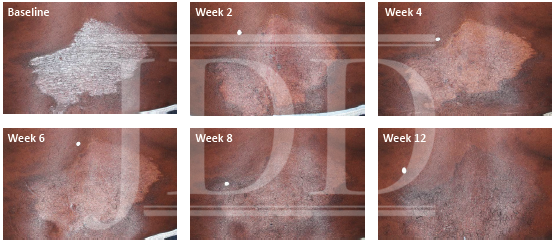

The patient was a 58-year-old, non-Hispanic, Black male with moderate psoriasis (Investigator’s Global Assessment [IGA]=3) and affected body surface area (BSA) of 10% at baseline (Table 1). The patient was enrolled in a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled study that assessed HP/TAZ lotion in participants with moderate-to-severe psoriasis (NCT02462070); detailed methodology and study results have been previously published.14,15 The patient, randomized to HP/TAZ for 8 weeks with a 4-week posttreatment follow-up, was instructed to apply a thin layer of HP/TAZ lotion once-daily over all affected areas. The target lesion (Figure 1), located on the upper right arm, was 99 cm2 in size at baseline; prominent keloid scars were also apparent. The patient also had an additional non-target lesion treated with HP/TAZ during the study (Figure 2). At baseline, both lesions appeared as classic psoriatic elevated plaques covered with white/silvery scales. By week 2 of HP/TAZ treatment, scales had diminished, though affected skin was hypopigmented in the center with hyperpigmentation at the border of the psoriatic plaque resolution. The degree of hypopigmentation appeared to be greatest at week 4, with skin pigmentation nearing normal by week 8. At 4 weeks posttreatment, the affected skin area had returned to normal with small regions of hyperpigmentation, the greatest around the periphery of the affected skin lesion.

FIGURE 1. Target lesion. Patient was treated with HP 0.01%/TAZ 0.045% lotion once daily for 8 weeks, with 4-week posttreatment follow-up at week 12.

HP, halobetasol propionate; TAZ, tazarotene.

FIGURE 2. Additional lesion. Patient was treated with HP 0.01%/TAZ 0.045% lotion once daily for 8 weeks, with 4-week posttreatment follow-up at week 12.

HP, halobetasol propionate; TAZ, tazarotene.

The patient achieved treatment success with HP/TAZ lotion, with an improvement to ‘almost clear’ at week 4 that was maintained posttreatment at week 12 (Table 1). Improvements in affected BSA and signs of psoriasis at the target lesion were also observed early following treatment with HP/TAZ lotion and maintained up to 4 weeks posttreatment. The patient had substantial improvements in QoL during the study, with DLQI score decreasing from 9 (“moderate effect” on life) at baseline to 1 (“no effect” on life) at weeks 4 and 8.

No adverse events were reported. Dryness was the only local skin reaction present at baseline (assessed as moderate by the investigator), which subsided at weeks 2–6 and returned to mild dryness by study end (Table 1). No itching was reported during HP/TAZ treatment until posttreatment follow-up, where it was assessed as moderate. The patient did not report burning/stinging at any study visit. Further, there were no instances of skin atrophy, striae, telangiectasias, or folliculitis—other known drug-related skin reactions.

Discussion

Racial and ethnic differences in epidemiology, clinical features, genetic predisposition, and response to treatment of psoriasis are important to address given our increasingly diverse patient population.7 Here we report the management of psoriasis in a Black male enrolled in a clinical trial who was randomized to treatment with HP 0.01%/TAZ 0.045% lotion once daily for 8 weeks, with a 4-week posttreatment follow-up at week 12.

HP/TAZ was efficacious in this patient, who achieved an IGA score of 1 (almost clear) within 4 weeks and maintained treatment success at weeks 8 and 12. Affected BSA decreased 50% from baseline to week 8. Quality of life was improved in this patient, whose DLQI score by week 8 indicated “no effect” of psoriasis on the patient’s QoL, a substantial and clinically meaningful16 improvement from the “moderate effect” observed at baseline. A clinical feature of this patient was the presence of prominent keloid scars, which are benign fibrous growths resulting from an abnormal connective tissue response.17 While the cause of the keloids in this patient is not known, the presence of keloids is not unexpected, as there are racial differences in prevalence, with Black individuals forming keloids more often than White individuals.17

The patient experienced dyspigmentation of the affected skin during the trial, which is also not unexpected, given that resolution of psoriasis in darker skin is associated with both hypo- and hyper-pigmentation.18 Dyspigmentation is of particular concern, as it can have significant psychosocial impacts, contribute to greater negative emotions, and even be more bothersome than the psoriasis itself in patients with skin of color.2,4,7 Hypopigmentation was primarily experienced from weeks 2-8, with the greatest degree at week 4. By week 12 the affected skin area had returned to normal, with only small regions of hyperpigmentation, primarily around the periphery of the lesion. This relatively fast time to resolution is notable given that dyspigmented patches can take between 3 and 12 months to resolve.2

Skin color is primarily due to the presence of melanin, a pigment formed by immune cells called melanocytes. Melanin formation, or melanogenesis, is a complex process of melanin synthesis, transport, and release to keratinocytes, which occurs within organelles of melanocytes called melanosomes.19 The mechanisms and pathogenesis of postinflammatory hypo- and hyperpigmentation in psoriasis are not fully elucidated, though multiple hypotheses have been suggested. Inflammation-associated hypopigmentation may be a result of rapid turnover of keratinocytes during hyperplasia, which can interfere with melanosome transfer.18 Cutaneous inflammation, through signaling of growth factors and pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-17 and TNF-α, can also lead to hypopigmentation through inhibition of melanogenesis, 18,20 with more severe inflammation potentially leading to permanent pigmentary changes through loss or death of melanocytes.20 Interestingly, it has been observed that while hypopigmentation often accompanies active inflammation, patients are at risk of developing hyperpigmentation once the inflammation has resolved, potentially due to increased numbers and activity of melanocytes.18,21 This too may be the result of cytokine signaling during inflammation. For example, IL-17 and TNF-α can simultaneously suppress melanogenesis while also stimulating the proliferation of melanocytes; as such, upon resolution of inflammation, the increased number of melanocytes in lesional skin (without concurrent suppression of melanogenesis) will produce excess melanin, leading to postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.18

The fixed combination of HP and TAZ used to treat psoriasis in the patient from this case report resulted in psoriasis lesion clearance with self-limited postinflammatory hypopigmentation and low levels of hyperpigmentation observed by week 12. Topical corticosteroids, a mainstay of treatment for psoriasis,8 are used as first-line therapy for hyperpigmentation when combined with hydroquinone and topical retinoids.5,22 Corticosteroids are thought to be effective by decreasing cellular metabolism, thereby inhibiting melanin synthesis.22 Corticosteroids have also been shown to minimize the risk of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation after laser resurfacing.23 Topical retinoids are effective in treating postinflammatory hyperpigmentation with other agents as described above or as monotherapy.22 For example, TAZ 0.1% gel and cream have demonstrated efficacy in acne-related postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, significantly improving pigmentation intensity versus vehicle24,25; TAZ was also more effective than adapalene 0.3% gel in reducing hyperpigmentation.25 Tazarotene 0.1% cream is approved as an adjunctive treatment in the mitigation of facial mottled hyper- and hypopigmentation. Retinoids are thought to reduce hyperpigmentation through multiple mechanisms, including: stimulating keratinocyte turnover (promoting loss of melanin), reducing/inhibiting melanosome transfer to keratinocytes, and interrupting melanin synthesis.22,26 TAZ has also been shown to downregulate markers of cell proliferation and inflammation such as IL-6,12,13 which is known to have hypopigmenting effects.18

The fixed combination HP 0.01%/TAZ 0.045% lotion used by the patient in this case report has additional efficacy and safety benefits. The new polymeric emulsion technology used to develop HP/TAZ lotion allows for efficient permeation of the active ingredients into the dermal layers, at around half the concentration of traditional topical formulations.10 Further, HP/TAZ lotion has demonstrated synergistic activity, with efficacy greater than that which would be predicted from the individual active ingredients.10 The maintenance of therapeutic effect seen in this patient—who sustained disease reduction 4 weeks posttreatment—is likely due to the mechanism of action of TAZ in psoriasis, which restores skin to a quiescent, prelesional status.27 However, when used alone, TAZ can cause cutaneous irritation; HP alone can also result in AEs that limit long term use. These safety limitations can be minimized when combining HP with TAZ.10,11 The patient in this case report did not report any adverse events—including any application or irritation events—and local skin reactions were limited. Though the patient was limited to 8-weeks of HP/TAZ treatment as part of the clinical trial design, treatment with HP/TAZ for up to 1 year (maximum 24 weeks of continuous use) in an open-label, long-term study (NCT02462083) has demonstrated a favorable safety profile.28

Conclusion

In conclusion, this case report in a Black male patient demonstrates that this new formulation of HP 0.01%/TAZ 0.045% lotion was efficacious in the treatment of psoriasis, with treatment success achieved early and maintained 4 weeks posttreatment. Hypopigmentation was evident during resolution of disease, though had completely resolved by week 12 with minimal hyperpigmentation observed. These results indicate that HP/TAZ may be a treatment option for patients with skin of color, who are disproportionally affected by postinflammatory dyspigmentation.

Disclosures

Seemal Desai has served as a research investigator and/or consultant for Skinmedica, Ortho Dermatologics, Galderma, Pfizer, Dermavant, Almirall, Dermira, and Watson.

Andrew F. Alexis has received grant/research support (funds to institution) from Leo, Novartis, Almirall, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Celgene, Menlo, Galderma, Bausch Health, and Cara; and has served as a consultant/advisory board member for Leo, Novartis, Menlo, Galderma, Pfizer, Sanofi-Regeneron, Dermavant, Unilever, Celgene, Beiersdorf, L’Oreal, BMS, Menlo, Scientis, Bausch Health, UCB, and Foamix.

Abby Jacobson is an employee of Ortho Dermatologics and may hold stock and/or stock options in its parent company.

Acknowledgements

The studies were funded by Ortho Dermatologics. Medical writing support was provided by Prescott Medical Communications Group (Chicago, IL) with financial support from Ortho Dermatologics. Ortho Dermatologics is a division of Bausch Health US, LLC.

References

10. Tanghetti EA, Stein Gold L, Del Rosso JQ, et al. Optimized formulation for topical application of a fixed combination halobetasol/tazarotene lotion using polymeric emulsion technology. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019:1-8.

16. Basra MK, Salek MS, Camilleri L, et al. Determining the minimal clinically important difference and responsiveness of the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI): Further data. Dermatology. 2015;230(1):27-33.

Originally published in the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology in October 2020.

Desai, S. R., Alexis, A. F., & Jacobson, A. (2020). Successful Management of a Black Male With Psoriasis and Dyspigmentation Treated With Halobetasol Propionate 0.01%/Tazarotene 0.045% Lotion: Case Report. Journal of drugs in dermatology: JDD, 19(10), 1000-1004. https://jddonline.com/articles/dermatology/S1545961620P1000X

Content and images republished with permission from the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology.

Adapted from original article for length and style.

The Journal of Drugs in Dermatology is available complimentary to US dermatologists, US dermatology residents, and US dermatology NP/PA. Create an account on JDDonline.com and access over 15 years of PubMed/MEDLINE archived content.

Did you enjoy this case report? You can find more here.