Hypopigmented patches and plaques are a rare presentation of cutaneous sarcoidosis. JDD authors describe a case of generalized hypopigmented cutaneous sarcoidosis that showed good response to minocycline therapy.

Introduction

A 58-year-old African-American male with a past medical history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, tobacco use, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency, and hyperlipidemia presented with a two-year history of asymptomatic light spots on his trunk and upper extremities. He reported a history of cutaneous sarcoidosis a decade prior, characterized by erythematous papules and plaques that had regressed with hydroxychloroquine therapy. The newer light patches were not responsive to mid-potency topical steroids or tacrolimus 0.1% ointment. Review of systems was negative. The patient denied any new medications or history of travel outside of the metropolitan area.

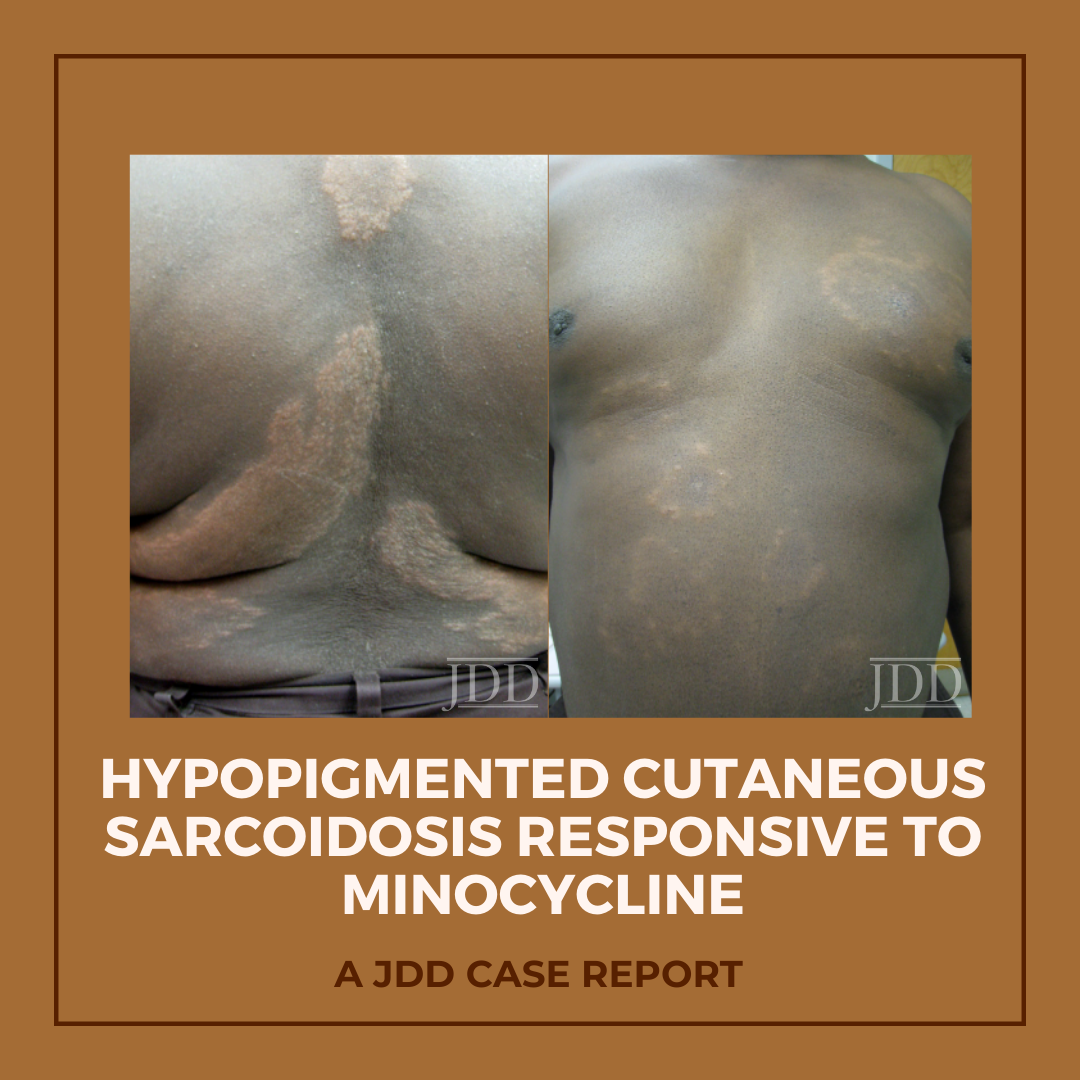

Physical examination of the skin was significant for multiple hypopigmented patches on the face, neck, and extremities; hypopigmented plaques on the back (Figure 1); and annular plaques of hypopigmented papules on the chest and abdomen (Figure 2). The lesions were not hypoesthetic. There was no lymphadenopathy and physical exam was otherwise unremarkable.

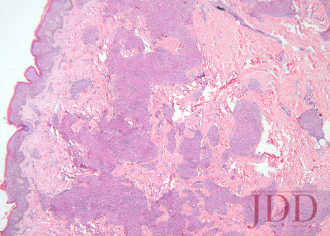

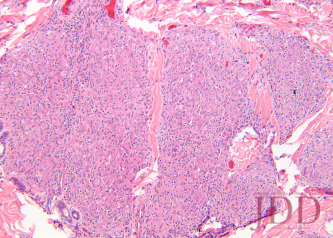

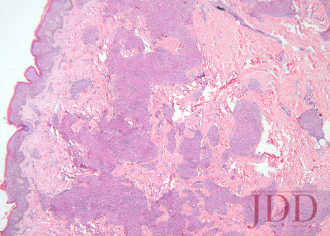

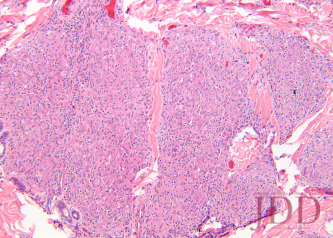

A biopsy from the left arm showed a superficial and deep multinodular granulomatous infiltrate sparing the epidermis (Figure 3). The granulomas were predominantly composed of epithelioid histiocytes with a few scattered lymphocytes (Figure 4). Special stains for microorganisms were negative. There was no appreciable epidermal change or pigment incontinence. The histopathological picture was consistent with recurrent cutaneous sarcoidosis.

Computed tomography of the chest with and without contrast showed no evidence of active pulmonary sarcoidosis or lymphadenopathy. An ophthalmologic exam, abdominal ultrasound, and spirometry were within normal limits, as were serum cal cium and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) levels.

Because the patient’s skin manifestations had resolved with hydroxychloroquine in the past, this treatment was restarted at 200 mg twice-daily. Unfortunately, laboratory monitoring revealed hepatic transaminitis and mild anemia 2 months into the treatment course, corresponding with only minimal improvement of the hypopigmented plaques, necessitating discontinuation of hydroxychloroquine. Minocycline at a dose of 100 mg twice daily was then initiated 4 months after normalization of liver function tests. After 5 months of treatment, all hypopigmented patches, papules, and plaques had completely or partially repigmented and were appreciably smoother and flatter (Figures 5 and 6). The patient tolerated the medication well with no adverse effects.

FIGURE 1. Hypopigmented plaques over the back.

FIGURE 2. Hypopigmented annular plaques of papules on the abdomen.

FIGURE 3. Hematoxylin and eosin stain of a left arm skin biopsy show-ing dermal granulomatous inflammation.

FIGURE 4. Hematoxylin and eosin stain of a left arm skin biopsy at higher magnification demonstrating well-formed naked granulomas.

FIGURE 5. Flattening and repigmentation of plaques on the back after treatment with minocycline.

FIGURE 6. Repigmentation of annuli on the anterior trunk after treat-ment with minocycline.

Discussion

The skin is one of myriad organs potentially affected by sarcoidosis, a multisystem idiopathic disorder characterized histologically by infiltration of noncaseating granulomas. Cutaneous manifestations of sarcoidosis are protean, including papules and plaques of various morphology and distribution, subcutaneous nodules, pruritus, ichthyosis, erythroderma, ulceration, verrucosis, nail disease, and infiltrative scars.1 In the United States, sarcoidosis is more common in African-Americans than in other ethnic groups, and cutaneous manifestations in individuals of African descent are more likely to be atypical.2

In 1973, Cornelius et al reported 4 patients who presented with hypopigmented and depigmented patches and plaques that showed the naked tuberculoid granulomas characteristic of sarcoidosis on skin biopsy.3 The distribution in these cases was variable, with generalization in one patient and localization to the face, legs only, or legs and arms in the other three. Histologically, no difference in epidermal melanocyte count was noted between affected and unaffected skin, but relative hypomelanosis of the malphigian and corneal layers was appreciated. All patients had multisystem disease. Four years later, Hubler described a “hypomelanotic canopy” in a woman with lupus pernio and lymphadenopathy whose hypopigmented patches overlay deep subcutaneous nodules on the arms.4Biopsy of an enlarged lymph node revealed epithelioid granulomas that were reduplicated on skin biopsy. Interestingly, cutaneous hypopigmentation lacking any histological evidence of granulomatous dermatitis has also been observed in the setting of systemic sarcoidosis;5,6 this highlights the need for vigilant continued surveillance when the clinical index of suspicion for sarcoidosis is high and biopsy is noncorroborative.

The etiopathogenesis of hypopigmentation in sarcoidosis, like the disease itself, is unknown. Theories regarding the likely mul tifactorial cause of sarcoidosis center around T-cell—mediated autoimmunity, genetic predisposition, and aberrant response to bacterial or other antigens; the evidence for each has been extensively reviewed elsewhere.1,7 The rare cutaneous hypopigmentation seen in dark-skinned individuals with sarcoidosis appears to represent a melanopenic hypomelanosis, as opposed to postinflammatory hypopigmentation or melanocytopenia.3,4,8 In our patient, there were no epidermal changes, interface in flammation, or melanin-containing dermal macrophages to suggest postinflammatory dyspigmentation.

Minocycline represents an attractive alternative treatment for chronic sarcoidosis in patients who might otherwise be treated with long-term corticosteroids, antimalarials, methotrexate, or other immunosuppressants. The tetracycline class of antibiotics has previously demonstrated utility in a variety of dermatoses and autoimmune-connective tissue diseases, and may be particularly efficacious for granulomatous skin conditions.9,10 Tetracyclines have specifically shown efficacy in the treatment of granulomatous periorificial dermatitis, cheilitis granulomatosa, granulomatous rosacea, and silicone granulomas.11-14 More recently, tetracyclines proved beneficial in treating granuloma annulare (GA), an entity often with significant clinicopathological overlap with cutaneous sarcoidosis.15,16 Marcus et al showed that, in combination with rifampin and ofloxacin, 3 to 5 courses of monthly minocycline therapy led to complete clearance of GA in 6 patients, half of whom had generalized disease.15 In this series, the rationale for selection of the same triple combination antimicrobial therapy as that used for paucibacillary leprosy (PBL) was that the clinical and histological similarities between PBL and GA might impart an equally similar response to treatment. The same logic could be extrapolated further to include patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis as candidates for a treatment regimen, including minocycline, with or without rifampin and ofloxacin.

Minocycline as monotherapy was efficacious for the treatment of chronic cutaneous sarcoidosis in an open observational study of 12 patients by Bachelez et al.17 The cutaneous manifestations of patients in the Bachelez group included classic plaques, papulonodules, subcutaneous nodules, and lupus pernio. Ten of 12 patients completely or partially responded to treatment, which was generally well tolerated except for drug hypersensitivity syndrome in one patient with a history of other autoimmune diseases. Park et al later reported a patient with cutaneous, lacrimal gland, pulmonary, and ocular (choroidal) sarcoidosis that responded to minocycline.18

Miyazaki et al described a patient with a unique presentation of muscular sarcoidosis of the limbs, as well as uveitis and pulmonary disease, in whom clinical response to minocycline was paralleled by normalization of an elevated ACE level.19 The patient relapsed off of minocycline, but rapidly responded to reintroduction of the medication. Immunohistochemical staining of muscle biopsy specimens for Propionibacterium acnes showed multiple small particles within granuloma macrophages and giant cells, substantiating the theory that sarcoidosis is an infectious disease or an aberrant immunologic response to bacteria. Evidence for the role of other infectious agents in sarcoidosis, especially Mycobacterium tuberculosis, has been mixed and inconclusive.20 That sarcoidosis is purely an infectious disease is certainly within the realm of possibility,21 but the recurrence of disease once antibiotics are discontinued argues against this theory.19 An alternative explanation is that the benefits of tetracyclines in sarcoidosis and other autoimmune diseases are derived more from their nonantibiotic immunomodulating properties. The anti-inflammatory properties ascribed to minocycline include inhibition of T cell activation, proliferation, and transmigration as well as expression of nitric oxide synthetase and matrix metallopeptidase 9 (MMP-9).9Furthermore, tetracyclines have been shown to inhibit granuloma formation in vitro.22

Conclusion

The role of tetracyclines in the therapeutic armamentarium of sarcoidosis, especially in those who cannot tolerate antimalarials or other immunomodulating medications, is likely to expand. Whether minocycline is particularly effective for the hypopigmented variety of cutaneous sarcoidosis remains to be seen.

Disclosures

The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- English JC 3rd, Callen JP. Sarcoidosis. In: Callen JP, Jorizzo JL, Bolognia JL, et al, eds. Dermatological Signs of Internal Disease. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2009:287-295.

- Jayck WK. Cutaneous sarcoidosis in black South Africans.Int J Dermatol. 1999;38(11):841-845.

- Cornelius CE 3rd, Stein KM, Hanshaw WJ, Spott DA. Hypopigmentation and sarcoidosis. Arch Dermatol.1973;108(2):249-251.

- Hubler WR Jr. Hypomelanotic canopy of sarcoidosis. Cutis.1977;19(1):86-88.

- Alexis JB. Sarcoidosis presenting as cutaneous hypopigmentation with repeatedly negative skin biopsies.Int J Dermatol. 1994;33(1):44-45.

- Hall RS, Floro JF, and King LE Jr. Hypopigmented lesions in sarcoidosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11(6):1163-1164.

- English JC 3rd, Patel PJ, Greer KE. Sarcoidosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44(5):725-743.

- Clayton R, Breathnach A, Martin B, et al. Hypopigmented sarcoidosis in the Negro. Report of eight cases with ultrastructural observations. Br J Dermatol.1977;96(2):119-125.

- Sapadin AN, Fleischmajer R. Tetracyclines: nonantibiotic properties and their clinical implications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(2):258-265.

- Stone M, Fortin PR, Pacheco-Tena C, Inman, RD. Should tetracycline treatment be used more extensively for rheumatoid arthritis? Metaanalysis demonstrates clinical benefit with reduction in disease activity J Rheumatol.2003;30(10):2112-2122.

- Falk ES. Sarcoid-like granulomatous periocular dermatitis treated with tetracycline. Acta Derm Venereol.1985;65(3):270-272.

- Camacho F, García-Bravo B, and Carrizosa A. Treatment of Miescher’s cheilitis granulomatosa in Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol.2001;15(6):546-549.

- Mullanax MG, Kierland RR. Granulomatous rosacea. Arch Dermatol. 1970;101(2):206-211.

- Senet P, Bachelez H, Ollivaud L, Vignon-Pennamen D, Dubertret L. Mi- nocycline for the treatment of cutaneous silicone granulomas. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140(5):985-987.

- Marcus DV, Mahmoud BH, Hamzavi IH. Granuloma annulare treat- ed with rifampin, ofloxacin, and minocycline combination therapy Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(7):787-789.

- Duarte AF, Mota A, Pereira MA, Baudrier T, Azevedo F. Generalized granuloma annulare—response to doxycycline.J Eur Acad Derma- tol Venereol. 2009;23(1):84-85.

- Bachelez H, Senet P, Cadranel J, Kaoukhov A, Dubertret L. The use of tetracyclines for the treatment of sarcoidosis.Arch Dermatol. 2001;137(1):69-73.

- Park DJ, Woog JJ, Pulido JS, Cameron JD. Minocycline for the treatment of ocular and ocular adnexal sarcoidosis.Arch Ophthal- mol. 2007;125(5):705-709.

- Miyazaki E, Ando M, Fukami T, Nureki S, Eishi Y, Kumamoto T. Mi- nocycline for the treatment of sarcoidosis: Is the mechanism of action immunomodulating or antimicrobial effect? Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27(9):1195-1197.

- Tchernev G. Cutaneous sarcoidosis: the “great imitator”: etiopathogenesis, morphology, differential diagnosis, and clinical management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7(6):375-382.

- Marshall TG, Marshall FE. Sarcoidosis succumbs to antibiotics—implications for autoimmune disease.Autoimmun Rev.

- Webster GF, Toso SM, and Hegemann L. Inhibition of a model of in vitro granuloma formation by tetracyclines and ciprofloxacin. Involvement of protein kinase C. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130(6):748-752.

Originally published in the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology in April 2012.

Schmitt, C. E., Fabi, S. G., Kukreja, T., & Feinberg, J. S. (2012). Hypopigmented cutaneous sarcoidosis responsive to minocycline. Journal of drugs in dermatology: JDD, 11(3), 385-389. https://jddonline.com/articles/dermatology/S1545961612P0385X

Content and images republished with permission from the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology.

Adapted from original article for length and style.

The Journal of Drugs in Dermatology is available complimentary to US dermatologists, US dermatology residents, and US dermatology NP/PA. Create an account on JDDonline.com and access over 15 years of PubMed/MEDLINE archived content.

Did you enjoy this case report? You can find more here.